The West End Victorian theatres formed an interaction between the actors and the audience as well as the architecture of the theatre itself. Upon entering the Lyceum, H. A. Saintsbury declared that "the spirit gripped you: it had enveloped you before you took your seat, gas-lit candles in their wine-coloured shades glowed softly on the myrtle-green and cream and purple with its gilt mouldings and frescoes and medallions . . You were in the picture, beholding, yet part of it.1

Going to the theatre is as important as the play you are going to see. The theatre's architecture, the audiences' attire, the "stage" all providing an expression of the social and cultural times as well as theatrical.

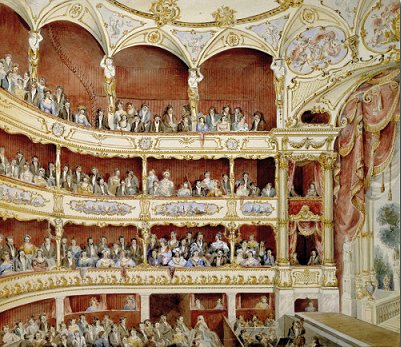

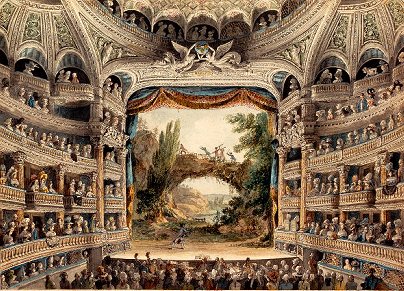

Theatre design remained the same for over 150 years. The audience sitting in the pit, facing the stage, which is surrounded on three sides by an audience seated in boxes. Some featured balconies above the boxes divided into more boxes and galleries, the size dependent upon the individual theatre. General seating (excluding the boxes) was unreserved and the spectators viewed the performance sitting on backless benches and chairs. (St. James Theatre by Crace)

Theatre design remained the same for over 150 years. The audience sitting in the pit, facing the stage, which is surrounded on three sides by an audience seated in boxes. Some featured balconies above the boxes divided into more boxes and galleries, the size dependent upon the individual theatre. General seating (excluding the boxes) was unreserved and the spectators viewed the performance sitting on backless benches and chairs. (St. James Theatre by Crace)

Using iron and support posts, builders were able to create theatres which held thousands of people which was supported by the increased city population and the investors' expectations of growing audiences. The Drury Lane (West End) had a capacity of 3,600. Other large theatres were built, but away from the West End to attract the lower middle and working classes. The Britannia seated 3,900 and Ashley seated 3,800; the Pavilion at 3,500, the Standard at 3,400 and the Victoria at 3,000. To allow for the additional capacity, the balconies were deepened and extend above the pit using iron trusses, stanchions and girders. By the early 1870s, however, concern was raised over safety due to fire as almost 26 theatres were destroyed by fire between 1839 and the 1870s. These concerns resulted in requirements which forced the reduction of capacity as well as required fireproofing and better and additional exits.

Despite the theatre's size, however, the design remained generally the same consisting of a lower floor of stalls and pit extending under the dress circle and additional balconies wrapped around and above the lower floor.

Particularly interesting to note is that the Victorian theatre is always well lit as it would be a pity if others could not see the fashionable and very expensive outfits the upper class attendees were wearing. In fact, there was quite a stir when the lighting was dropped for the staging of Wagner's "Ring". Unfortunately the brighter lighting also added to the "noise" in the theatre as the light encouraged chatting, while darkness did not. And the backless benches and chairs were gradually being replaced around the middle 1840s to ones with backs for the purpose of increasing personal comfort.

The Stage

The Victorian stage is inherited from the 18th century and features a rectangular proscenium opening, and behind it a working space larger than the auditorium itself.

The Victorian stage is inherited from the 18th century and features a rectangular proscenium opening, and behind it a working space larger than the auditorium itself.

Above the stage and hidden from view is the gridiron. It is here where machines were placed which used pulleys to lift the play's characters giving the appearance of flying. All the equipment is managed by hand resulting in a large number of stage crew. At the lowest level of this area a series of grooves allowed for the scenery to be slid on and off as required. This system, however, is starting to disappear in lieu of "flown" scenery and free-standing scenes secured to the stage floor by braces or mounted on wheeled platforms.

Machinery below the stage is just as important as that above it as it was used to give the appearance of scenery or characters disappearing below the stage. The noise created by this equipment is a bit disturbing and the orchestra compensates for this noise by playing extraordinarily loud during scenery changes.

Scene Painting

The resident scene painter(s) (some of the famous being the Grieves and the Telbins) are valuable members of the theatre company as it is their job to produce scenery that not only represented the play, but also an impression of the real world. And as scenery went from being two-dimensional to three-dimensional, the more valuable the artist.

First, the scenery had to be sketched and then turned into a prototype model to insure that the composition, colouring and lighting all worked as one to create the scene desired. This model was then in turn recreated into a frame approximately 40' wide by 25' high. To these frames would be attached gauzes, linen and muslin on which the scene was painted.

Lighting

When it came to lighting, the Victorians were less resistant to change. Lighting went from candles to oil and gas lamps to electricity in two generations. Prior to gas lamps, the theatre stages were lit by a combination of wax candles and oil-burning lamps for the footlights and in the wings. Gas-lit chandeliers supplied light to the main auditorium and this light was left on during the performance, though it sometimes was lowered to create a ghostly image or moonlit scene.

Sound Effects

Until the 1890s, sound effects were all produced traditionally. Thunder was created by rolling a sheet of iron or rolling cannon balls down a wooden trough. A rumbling vibration was created by striking a big wooden drum with the skin tightly stretched over it. Wind was created using a wind machine which resembled a paddle-steamer wheel. Rain was made by crushing dried peas into a wooden box and shaking it.

Technical Rehearsals

Prior to the dress rehearsal, a technical rehearsal would be made, supervised by the theatre manager, to insure that all the scenery and lighting worked properly. Any special effects would also be tested at this time.

Back to Intro/Index or Site Map

| | Family Gallery | Servants Parlour | Tour Home | Typical Day | Etiquette | Shopping Trip | |

| | Victorian Christmas | Victorian England Fun and Games | Ashton Library | Victorian Wedding | |

| | Victorian England Overview | Guest Registry | Honorary Victorian | Tours | |

| | Awards Received | Bibliography | |

| | 1876 Victorian England Home | |

Credits below copyright information |

| Contact

webmaster |

| Copyright

1999-2017 All Rights Reserved - B. Malheiro May not be reproduced in any way without express written permission of webmaster. |

Credits:

Background and buttons are the creation of webmaster, B. Malheiro. These images have been watermarked and are not for use on another site. Site authored by webmaster.

1. Irving as Stage Manager We Saw Him Act, ed. H. A. Saintsbury and Cecil Palmer (London 1939) p. 396.